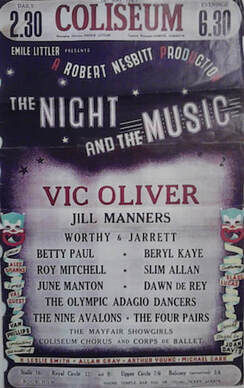

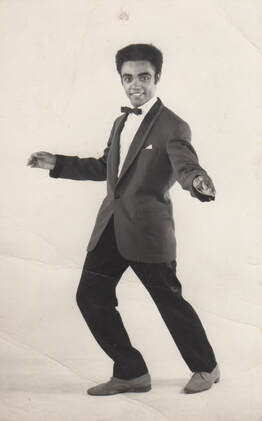

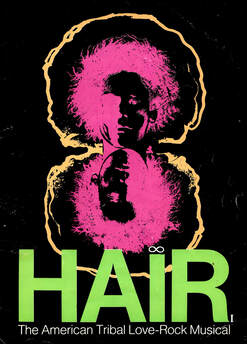

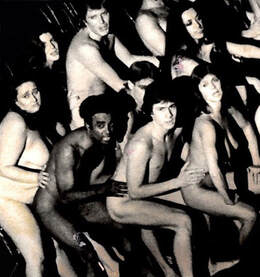

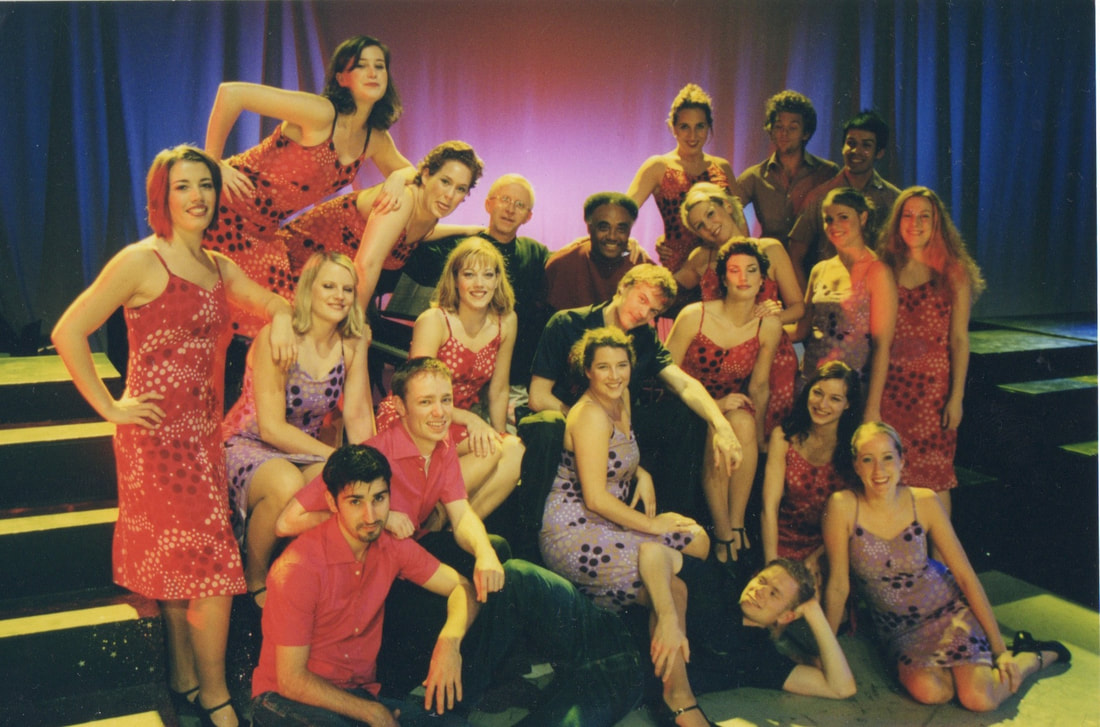

A LIFE IN THE THEATRE

In March 2006, Johnny Worthy gave a talk to Brighton & Sussex Equity about his life in showbiz.

Herewith reproduced, with a few amendments and updates, is the account originally published

in the branch newsletter...

Herewith reproduced, with a few amendments and updates, is the account originally published

in the branch newsletter...